What happens when a politician’s interest diverges from his party’s interests? That’s the question facing the Democratic Party, and it is the subject of today’s newsletter.

President Biden has survived the initial fallout from his shocking debate performance last month, and the momentum against him within the Democratic Party appears to have slowed. But the party’s basic problem is unchanged: His presence on the ballot seems likely to hurt the Democrats’ chances of beating Donald Trump this fall — and hurt the party’s chances of controlling Congress.

Among the evidence: In public appearances, Biden continues to confuse facts, and he struggles to make clear arguments for his candidacy. About 75 percent of voters say he is too old to be president, polls show. Most Democratic voters don’t want him to be the nominee, polls also show. His approval rating is below 40 percent, worse than any modern president who has gone on to win re-election.

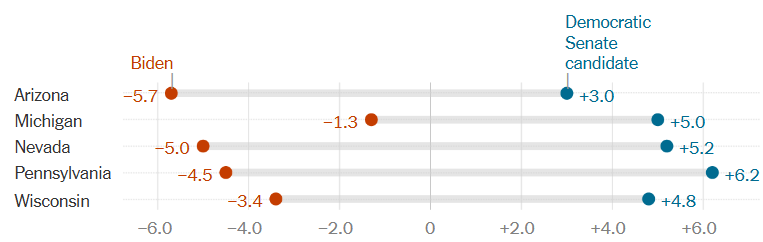

Notably, in every battleground state that has a Senate race this year, the Democratic Senate candidate is winning, and Biden is losing:

Biden vs. Democratic Senate candidates

Polling lead or deficit, in percentage points

In an earlier era, when the country’s political parties were stronger, Democratic officials might have forced Biden from the race. In 1974, senior Republicans famously persuaded Richard Nixon to resign. In 1944, when Franklin Roosevelt was ailing, Democratic power brokers ousted his Soviet-friendly vice president, Henry Wallace, from the ticket and replaced him with Harry Truman.

Today, the parties are weaker, and Democratic officials seem loath to confront Biden. (Daniel Schlozman, a political scientist at Johns Hopkins, argued in a recent Times Opinion essay that Democratic delegates do have the power to replace Biden.) For now, Democrats find themselves with a nominee whom most of them don’t want, and they don’t know what to do about it.

Polls, misrepresented

Near the end of Biden’s press conference last week, he gave an answer that highlighted the difference between his own interests and his party’s.

It came after a reporter asked him about the possibility that Vice President Kamala Harris would replace him on the ticket. “If your team came back and showed you data that she would fare better against former President Donald Trump, would you reconsider your decision to stay in the race?” the reporter, Haley Bull of Scripps News, asked.

Biden replied: “No, unless they came back and said, ‘There’s no way you can win.’ Me. No one is saying that. No poll says that.”

It’s worth unpacking that response. Biden did not reply that he was the Democrat most likely to win. Indeed, he suggested he might remain in the race even if it helped Trump. He named an impossibly high bar — certainty of defeat — for quitting.

Four years ago, Biden probably was the Democrat with the best chance to beat Trump. Polls showed that Biden was a stronger candidate than his main primary rivals. But his standing has significantly weakened since then, as my colleague Nate Cohn has documented. The 2024 Biden no longer represents the promise of change. He is an unpopular and visibly aged incumbent.

Another telling sign is that Biden tends to misrepresent polls when he talks about them. He claimed in last week’s press conference that he beats Trump “all the time” in polls of likely voters. That is false; Trump tends to win polls of likely voters. Biden has also described the race as “a tossup”; most analysts disagree and consider Trump the favorite. At other times, Biden alleges that the polls are simply wrong, without explanation.

(Related: My colleagues report that Biden’s circle of confidants has shrunk in the past few weeks to a tiny group of loyalists.)

With all this said, there is at least one very good argument for why Biden should remain the nominee. He won the primaries, in a rout. “Look, 14 million people voted for me to be the nominee,” he told NBC News this week.

His critics can make counterarguments, though: that Biden minimized his public appearances before the primaries to hide his aging — and that Americans can’t unsee his debate performance. These changed circumstances explain why 20 congressional Democrats have called on him to quit and many more privately hope he does. “If he is our nominee, I think we lose,” Adam Schiff, a House Democrat running for Senate in California, said at a fund-raiser last weekend.

R.B.G. syndrome

Many Democrats are haunted by a recent experience with another member of their party who refused to retire.

Early in Barack Obama’s second term, Ruth Bader Ginsburg could have resigned from the Supreme Court and allowed Obama (and the Democratic-controlled Senate) to replace her. But she rejected pleas to do so, sometimes using dubious justifications. She claimed, for instance, that a similarly liberal justice couldn’t have been confirmed, even though the first justice Obama named to the court — Sonia Sotomayor — was arguably more liberal than Ginsburg.

The real explanation seemed to be that she enjoyed her powerful job, much as Biden does. She prioritized her personal interests over her political values. She risked policy changes she abhorred — like the demise of Roe v. Wade, causing the loss of abortion access for millions of women — to keep her job well into her 80s.

For Ginsburg’s fellow progressives, the result was tragic. Biden is evidently hoping that his similar decision leads to a different outcome.